Cliff Dale (Part I)

A “Cliff Notes” Story

November 2007

For most hikers familiar with the trails in the park, the signature former Palisades estate would have to be George A. Zabriskie’s “Cliff Dale.” The imposing, two-story gray stone ruins of the manor house foundation — built in 1911, the upper floors torn down by the WPA in 1939 — still loom along the Long Path about half a mile north of Alpine Lookout. (The ruins are hidden from motorists on the Parkway for most of the year, only to emerge like a ghost castle flickering into view for a moment or two as they speed by once the leaves have fallen.) Stone columns are scattered among the trees that are growing from the scalp of the ruins. At the feet of the ruins is a declivity in the cliff top in which hikers can still trace the outlines of a man-made pond, overgrown with brambles and vines.

Yet Zabriskie’s was not the first estate to be built at this site, roughly opposite Hillside Avenue in what would become the town of Alpine by 1911. An earlier incarnation of “Cliff Dale” had its tale related in Walker’s Atlas of Bergen County from 1876. That article is reprinted in its entirety here.

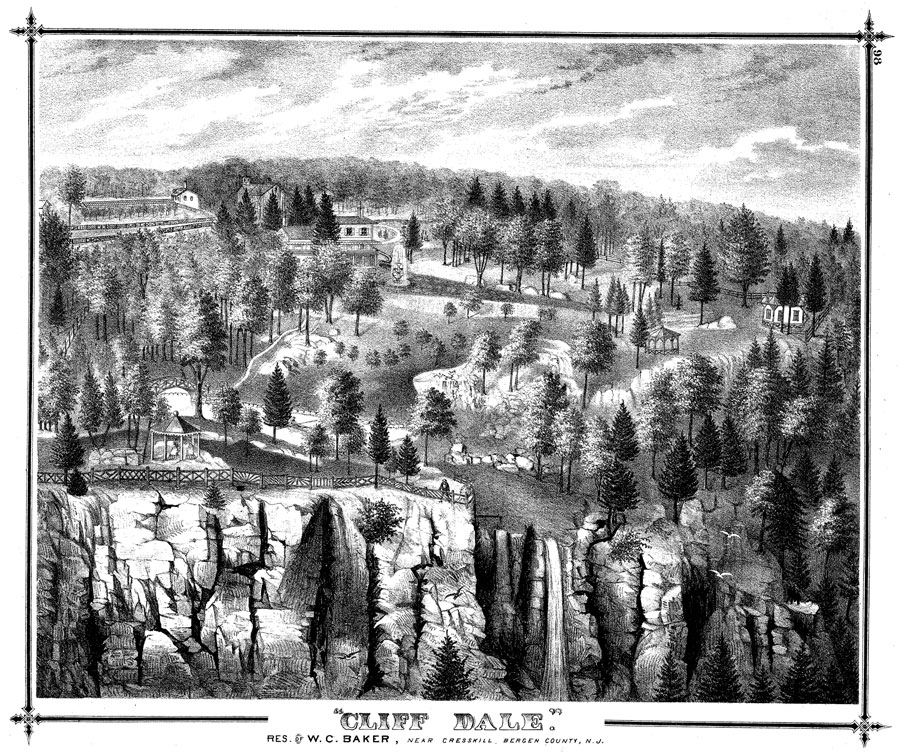

CLIFF DALE

The subject of our artist’s sketch on page 98, and the residence of W. C. Baker, Esq. (appropriately named from the peculiar combination of cliff and dale which makes the grounds so grandly beautiful), is situated on the border of the Palisades, overlooking the Hudson, fifteen miles from the City Hall in New York, directly opposite the city of Yonkers, and a little more than a mile from Cresskill Village, a station on the Northern Railroad. The beauty of the scenery and views from the grounds is simply grand. Plainly visible to the naked eye are Long Island and the Sound, and the different railroads winding between them and the observer. The top of the Palisades at this point is about five hundred feet above tidewater.

Mr. Baker’s first purchase here was made in 1871, since which he has purchased adjoining lands, adding to the beauty and value of his original grounds thereby.

Springs abound on the place, one in particular being strongly tinctured with iron and sulphur. From these springs, by means of steam apparatus, water is forced to all parts of the grounds, supplying houses, barns, and ponds, as well as for irrigation, and providing a sufficient supply for two beautiful fountains, the water from which forms the handsome little lake shown in the picture, and running from thence falls, broken into foam and spray, hundreds of feet to the river below. Mr. Baker also manufactures his own gas, which (with the water facilities and other conveniences) gives him all the advantages in that line to be derived from a residence in the city. Mr. Baker was born in the State of Maine, in the year 1828, and his attention was early called to the subject of heating and ventilating buildings. He has obtained patents on many different inventions of his own, the most important of which is the hot-water heater used in railroad coaches, both in this country and in Europe. He became so eminently successful with his inventions regulating heat that he was led to undertake the artificial hatching of eggs by producing and maintaining a heat corresponding exactly to that produced by the body of the fowls. It required the finest possible regulating medium to keep the heat just right, and Mr. Baker met with many disheartening failures in his experiments, all appliances known to the scientific world for testing temperature failing to be delicate enough for the work. This would have discouraged most men, but Mr. Baker, relying upon his own inventive genius, supplied the want, and now, by the aid of gas to produce the heat, and electricity to test and control it, he has made the “incubator” a perfect success. The present hatching capacity is about 200,000 eggs per year. Every egg is hatched with the precision and regularity of clock-work, and the chickens are removed to the breeding-house, which is also made to answer the purpose of a green-house, and is warmed by means of hot water contained in galvanized iron tanks, connected with which are cylinders of the same material, which run through the coops or pens on either side, and about two inches from the ground. These pipes or cylinders are wrapped in flannel, and the little chicks crawl under them, and evidently find them an admirable substitute for the mother hen

Heat from the pipes also warms the plants arranged on the shelves through the centre of the building, which is thirty by one hundred and fifty feet. Once each day the chickens are given cooked food. When three weeks old they are removed to other coops with cooler temperature. The hennery is a low building eight hundred feet in length, subdivided into numerous coops, each ten by twenty feet, and each provided with nests convenient to the passage-way, along which is laid an iron track with a small car used for carrying food and gathering eggs.

Among the different breeds of fowls [,] White Leghorns are preferred for market, and the Black Spanish for laying. Mr. Baker has demonstrated to the world that notwithstanding the numerous failures in this and other countries, hatching and rearing fowls by artificial heat is both practicable and profitable.

In a future story, we will chronicle the second incarnation of “Cliff Dale.” But we felt it important to set the scene with this account of Mr. Baker — and his “Cliff Dale,” that remarkable place where some 200,000 chickens a year once came home to roost…

– Eric Nelsen –