“Beyond the Reach of Devastation”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

September 2009

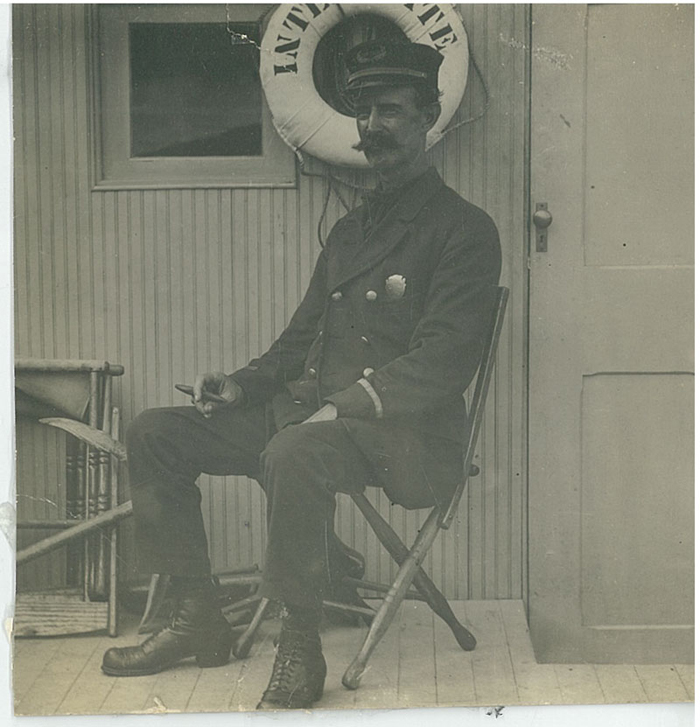

It was September 1909 and chairs were on J. DuPratt White’s mind. “In addition to the 36 camp chairs which you have ordered for the band,” the secretary of the Interstate Commission wrote to Captain John Jordan, their chief marshal at Alpine, “we will need 36 additional camp chairs for use on the boat.” Waturus, yacht of George W. Perkins, the New York president of the Commission, was to bring the governors to Alpine Landing on Monday morning; this was Wednesday. “You will please therefore arrange with your Yonkers man to have 36 camp chairs at the dock on Sunday morning. … It might be a good plan to have the [other 36] camp chairs for the band at the landing also delivered at the same time. They can all be stored on the ground floor of the house.” These past weeks Captain Jordan had been overseeing the fixing up of a rundown house at the Alpine docks, making it pretty for Monday’s exercise with the governors. (On the programs printed up for Monday they were calling it the “Old Cornwallis Headquarters”: there were stories around that the British general had stayed there in 1776; the locals for the most part just called it the old Kearney place.)

The “Hudson-Fulton Celebration” — marking the three-hundredth anniversary of Henry Hudson and his Half Moon and the hundredth, more or less, of Robert Fulton and his North River Steamboat of Clermont — a vast event, years in the planning — would begin in New York City that weekend. Millions would be coming to the city to view naval vessels from around the world (full-scale replicas of Half Moon and Clermont would look like toys alongside the modern battleships); then, through the next week, parades would clamber up the city’s avenues, fireworks would bedazzle the night sky, Wilbur Wright would fly around the Statue of Liberty — and the governors of New York and New Jersey would formally dedicate the Palisades Interstate Park, with its miles of dramatic riverfront so recently preserved.

“You of course understand,” Secretary White added, “that we need altogether 72 camp chairs…”

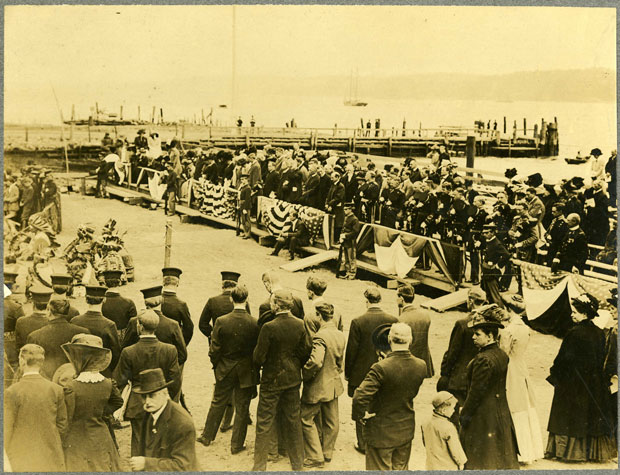

Around a thousand guests — among them fifty “mimic Indians” in headdress and blankets — greeted Waturus at Alpine Landing on Monday morning. The crowd formed in front of the little house: fresh white paint gleamed beneath the flags and bunting that Captain Jordan’s men had hung; the band sat upon their thirty-six camp chairs and played; and, as the benedictions and speeches began, a heavy sky promised at any moment to open up and drench the whole affair.

Colonel Edwin A. Stevens Jr., the New Jersey president of the Interstate Commission, presided, while New York president Perkins delivered the Commissioners’ Report; Dr. George F. Kunz of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society gave the keynote speech; New Jersey Governor J. Franklin Fort accepted the park on behalf of the people of his state and gave the Dedicatory Address. “As we stand in this old Cornwallis house,” Governor Fort proclaimed, “…unique, historic, we feel a thrill of patriotic purpose that the surroundings impart. Our fathers did much here in the days of the birth of the Republic. We, their descendants, honor them, and benefit ourselves, in preserving this park and these old buildings…”

Considered a century later, however, it was the speech by New York Governor Charles Evans Hughes that seems most striking, anticipating concerns more usually associated with the other end of the twentieth century. “About this river cluster the memories of our heroes of war and peace, and this beautiful valley is forever invested with the charm of the story of the vicissitudes of early settlements, of the struggle by which liberty was won, and of the marvelously expanding life of a free people,” Governor Hughes began; then went on: “It is fitting that at the outset we should turn from its historical associations to the river itself…

“… If we would preserve the resources of industrial power; if we would maintain proper regulation of the flow of our streams and make them agencies of progress rather than devastating forces, we must conserve the forests of this country. For a long period we were unmindful of reckless waste and greedy spoliation. We have not awakened too soon. In the State of New York in the last few years large areas of forest tract have been acquired. It is to be hoped these purchases will largely be extended. Provision should be made, too, for the improvement of the river, as a source of industrial power. Moreover, it should be kept free from pollution. We must maintain it as a wholesome river and not allow it to become a mere sewer. Of what avail material benefits, were it not for the opportunities to cultivate the love of the beautiful? …

“The highlands of the Hudson and these Palisades must be kept beyond the reach of devastation.”*

An American flag was run up the mast at the dock to join the pair of state flags there; the “Indians” danced; the Naval Reserve cutter Gloucester fired a cannon salute from the river; the concussions echoed off miles of newly-preserved cliff face; and Governor Hughes sped back down the river under his top hat to Spuyten Duyvil, where at two o’clock he was to lay the cornerstone to a monument for Henry Hudson. (It was there the sky kept its promise and everyone got drenched.)

The next day Secretary White wrote to Captain Jordan at Alpine: “Please go to the Riverdale dock with the boat” — Rana, the Park Commission’s police launch — “and get the [36] camp chairs which you will find with the Railroad agent…”

In February 1915 John Jordan was killed in a fall from the Palisades as he patrolled the park (a plaque on the Shore Trail marks near where his body was recovered). Colonel Stevens — whose father, Edwin Sr., had founded Stevens Institute of Technology and who himself, an engineer, developed the propeller-driven double-ended ferryboat — died in 1918. George Walbridge Perkins, for whom Perkins Memorial Tower at Bear Mountain would be named, continued his leadership of the Commission until his death in 1920. J. Franklin Fort died that same year. J. DuPratt White lived until 1939. In 1910, just forty-eight years old, Charles Evans Hughes would be appointed by President Taft to the United States Supreme Court; Hughes resigned in 1916 to become the Republican nominee for President, narrowly losing to incumbent Woodrow Wilson; President Harding appointed Hughes Secretary of State in 1921, and in 1930 President Hoover appointed him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, where he served until retiring in 1941. He died in 1948.

The “Old Cornwallis Headquarters” in time became the equally improbable “Blackledge-Kearney House” (it has since reverted to just the Kearney House). Beaches and campgrounds, bathhouses and CCC camps — picnic groves and boat basins and a “tourist camp” — much has come and gone. Some of the triumphalist language of 1909, too, can sound shopworn today, tinny. Yet beyond even the great cliffs themselves, something vital persists: a promise made, a promise to be kept.

Here’s to the next hundred years.

– Eric Nelsen –

*Different newspapers printed slightly different transcripts of the speeches made that day; the excerpt from Governor Hughes’s speech presented here is taken mostly from an article in the New York Times.