The Meaning of a Hut

A “Cliff Notes” Story

January 2001

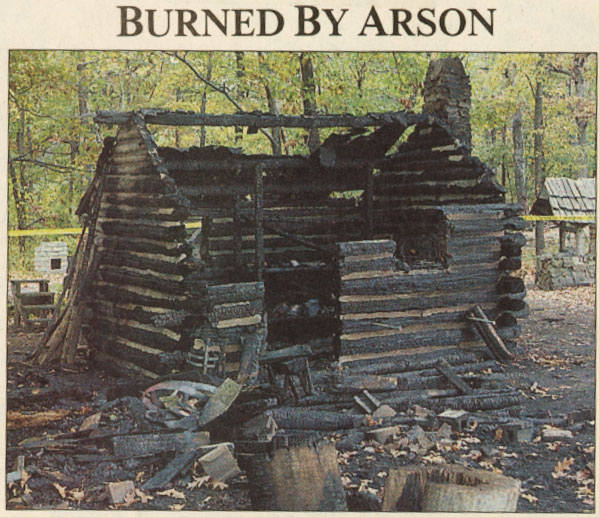

Just after two in the morning on Tuesday, October 31, a brushfire was reported on the Palisades south of the George Washington Bridge in Fort Lee Historic Park. The fire departments of several nearby towns responded, and the blaze was finally brought under control at 5:40 in the morning. Investigators later determined that it had spread from a woodshed by the Historic Park’s reconstructed “soldiers’ hut” and that the fire, which remains under investigation, had been deliberately set.

The soldiers’ hut, which measured nine feet by 12 feet and looked like a miniature log cabin, was also gutted, its contents destroyed in what the investigators feel was probably an act of “Mischief Night” vandalism. Only its stone chimney and portions of the walls were left standing.

The hut was a small structure — with a history all its own. It was built in 1980 by park staff and teenaged members of the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC). The woodshed and a well were built a year or so later, and an oven after that, also done with help from the YCC. The intent was to recreate the kind of encampment used by the garrison of the Continental Army stationed at Fort Lee before its abandonment in November, 1776. But this was not just “for show.” The hut and its accoutrements were intended from the start as a kind of working model, part of a one-of-a-kind “living history” program at the Historic Park.

“From the beginning, we didn’t want to do just a guided tour,” Historic Park director John Muller recalled recently. John began his career at the Historic Park shortly after it opened for the 1976 Bicentennial (see “Fighting for the Fort” for details of the effort to preserve the Fort Lee bluff). A talented teacher with a genuine love for his craft as well as a dedicated scholar of eighteenth-century life, John sought to combine his two passions into a unique program for schoolchildren. He envisioned a program in which participants would actually live in the eighteenth century for a few hours.

There were few blueprints for such a program 25 years ago, and the program needed to evolve with time. “We kept coming up with off the wall things to do,” John remembers with a chuckle. In addition to lessons on eighteenth-century military life, participants — called “recruits” in the program — would gather firewood, cook, learn about music, and in general immerse themselves in a total experience.

John and his staff sent out letters to schools in Bergen County describing the new program, and the first year of its existence they had classes come about once or twice a week. Thanks to word-of-mouth advertising from the teachers who participated that first year, the next year — and for each of the twenty years since — the program has been booked every day that it has been offered in the fall and spring, and the waiting list for classes wishing to book a program is about two years.

The program has averaged about fifty-two classes per year (programs are cancelled or rescheduled in severe weather) — more than a thousand classes, in other words. The yearly average is about 1,400 students, for a total of over 28,000 over the past two decades. (That is a number that might make Washington himself envious: it is more than twice the number of recruits in his actual Continental Army in 1776.)

In the course of five hours, under the supervision of John and his talented staff, the student recruits gather and chop firewood, cook a stew for lunch, march and drill, fire a cannon, set up a tent, make candles and musket balls, and learn a great deal about eighteenth-century life — and themselves. John and his staff also learn, and he says his favorite part of the program is “watching the kids work and listening to them at lunch — about how ‘hard’ it all is.” The same teachers tend to bring their classes back year after year. Throughout the day, the simple hut has served as a centerpiece of the program.

John describes the fire as “crushing” for him and his staff. “There were so many memories in the hut,” he recalled, “personal and professional.”

Like so many events of this type, however, there has been a bright side of sorts to the aftermath, in the form of a groundswell of public support for the Historic Park and the educational program. Donations — both in money and in offers of volunteer time to help rebuild the hut — have come in a steady stream since the story was first reported, and plans have been drawn to rebuild the hut in the spring. If resources permit, John hopes to add several other Revolutionary era structures as well.

When we visited John as we prepared this article, the first thing he did was to hand us a letter from his desk.

“This is what it all really means,” he said:

Dear Mr. Muller & Friends,

We were so sorry to hear about what happened to the fort. On behalf of all 5th graders at Honiss School [in Dumont, New Jersey], we would like to donate all of the $152.05 we made at our school bake sale. We hope this makes your holiday season a little brighter.

Sincerely,

The Honiss 5th Grade Students

– Eric Nelsen –