Oysters “Not Less Than a Foot Long”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

August 2021

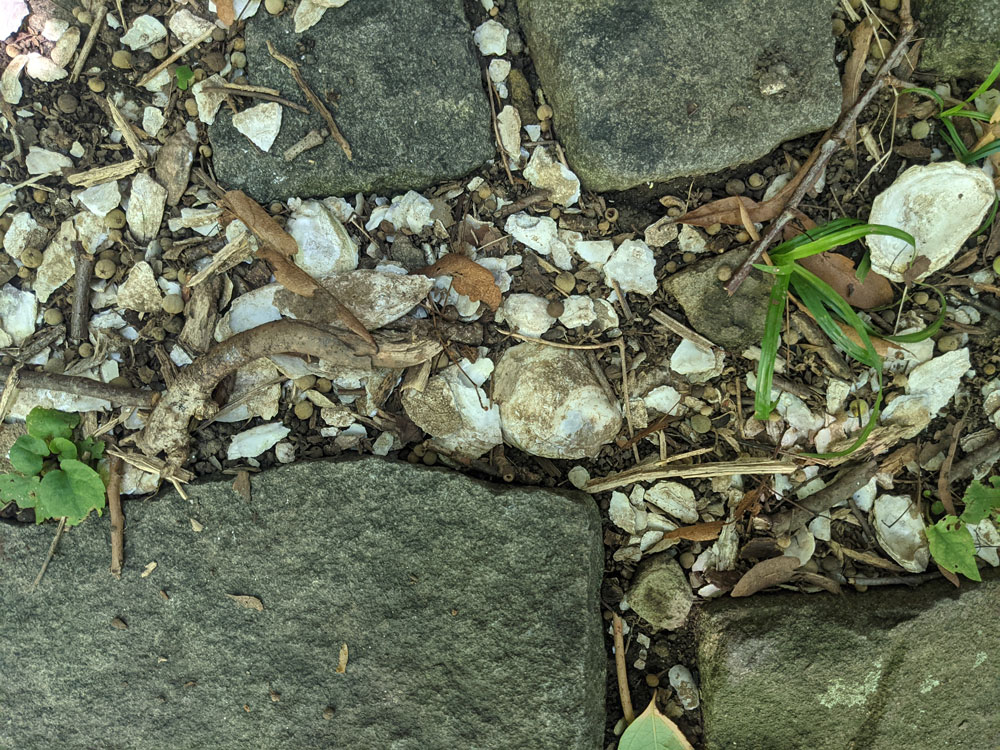

During our annual “Sea Glass Hunt!” hike, we lead families to a small beach along the Shore Trail in Alpine in search of the “sea glass” that washes up along the riverbank. Children with their plastic buckets and pails run up to us with their new treasures. In their tiny hands they hold colorful sea glass, which was discarded in the Hudson anywhere from ten to a hundred or more years ago, its sharp edges now worn smooth. Sometimes the children find broken pottery or even “sea bricks” (pieces of brick worn into round pieces). Occasionally, though, we see something more fragile than glass or ceramic remnants. Oyster shells, long empty and worn by the currents, can be spotted along with these man-made objects.

Oysters used to be a fundamental part of the Hudson and New York Bay, not only for human diets but also for the larger ecosystem. Oyster beds extended from the Hudson all the way out Long Island. They have long been absent from our scenery, however. They are, in fact, functionally extinct today, with only 0.01% of their previous population still living in the Greater New York waterways. What happened?

Before we answer that question, let’s look at what oysters do for the environments where they live. Oysters are a “keystone species,” meaning they help many other animals and plants thrive around them. These mollusks have hard shells to protect their invertebrate insides, and they tend to stick together, forming large reefs. They grow offshore in shallow water, where they act as a buffer between storm waves and the shoreline. Along with creating safe places for animals to live — and acting as fish nurseries — oysters are filter feeders that actively clean the water of sediment and debris. The more oysters, the cleaner the water surrounding them! When sunlight can reach below the waves, Sea grass and other plant life grows much better and can support more animals which feed on them. If that weren’t enough, oysters are nutritious — and therefore an important food source for many animals, including humans.

Oyster deposits in this park go back over 500 years to a time when the Lenape, our local indigenous group, used the oyster as a staple food. Archaeological evidence from old oyster deposits suggests that areas along the riverbank in the park were used as feasting sites for the Lenape or other local tribes.

In 1609, when the Half Moon sailed into what would become known as New York Harbor, Henry Hudson and his crew entered one of the world’s richest natural waterways. Whales, otters, sea turtles, and more were to be found here among the thriving oyster beds. Once Europeans began to colonize the area, they too ate these oysters in large amounts.

From the diary of Dutch Missionary Jasper Danckaerts, we learn that the Lenape and early New Amsterdam colonists prepared these oysters by wrapping them in seaweed and cooking them on an open fire:

They had already been thrown upon the [fire] to be roasted, a pail-full of Gouanes [Gowanus, i.e., Brooklyn] oysters, which are the best in the country. They are fully as good as those of England, and better than those of Falmouth [in England]. I had to try some of them raw. They are large and full, some of them not less than a foot long, and they grow sometimes ten, twelve, and sixteen together, and are then like a piece of rock.

Danckaerts noticed how these huge oysters were shaping the waterscape around them. These “pieces of rock” that he described helped form the very reefs that broke storm surges, saved the coastline from erosion, and protected nursery fish. He went on to note, “[the colonists] pickle oysters in small casks, and send them to Barbados and the other islands.” In fact, Pearl Street in lower Manhattan was named for the oyster shells that once littered its path. With reefs spanning over 220,000 acres, oysters were so abundant that they could support a growing population — as well as demand from the Caribbean!

But the oysters are not there now.

Due to over-cultivation by hungry New Yorkers who relied on them well into the early 1900s, the oysters could not keep up. The expansion of Manhattan Island (much of it done with rock quarried from the Palisades) would further disturb the already depleted oyster beds, while pollution in the river pushed the surviving reefs to the breaking point. But it wasn’t just here in the New York area: estimates suggest that over the last century 85% of the world’s oyster beds have gone. The reefs have disappeared, along with the plants and animals that depended on them. Our own park was not safe from the after-effects of human industry, and our last swimming beach closed after 1943 “due to river pollution caused by war conditions.” The Hudson was infamous for its levels of contamination well into the 1990’s.

Luckily, there are ways to help! The twelve miles of Hudson Riverfront that make up the Palisades Interstate Park in New Jersey are safe from development thanks to the foresight of those who founded it. Over the last fifty years, organizations such as Riverkeeper and Clearwater have educated and advocated for our local watersheds. Laws that were put in place thanks in large part to citizen advocates like the members of the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association help keep our rivers clean, in turn providing hospitable habitats for all sorts of plant and animal life. Today, the Hudson has cleaned up to the point where seals and the occasional whale are spotted in the Bay, along with sturgeons, eagles, and falcons. The Billion Oyster Project is trying to reintroduce oyster beds to the Greater New York Area, successfully releasing 24 million of them in 2019. They note that the oysters are surviving in the areas they are situated, even thriving. This alone, however, is not enough to sustain the ecosystem: as their literature explains, “Restoration without education is temporary.”

The key is to bring enthusiasm — and to share the important lessons learned from an unassuming mollusk.

– Francesca Costa –